SESTINA

While listening to the amazing poet Joy Harjo, she spoke about a poem about weaving that caught my attention. I dove into all sestina and instantly saw the connection. Patterns are patterns and if you know how to read them, you can apply them to your choice of material, whether its words, music, paint or yarn. Here under you’ll find a bite out of my desktop research journey.

Joy Harjo on Imagery and Form in Poetry

Source https://www.masterclass.com/classes/joy-harjo-teaches-poetic-thinking/chapters/imagery-and-form

I got inspired by Luci Tapahonso, the Navajo poet, wrote a poem on sestina about weaving. The Navajos are known for their weaving, and I thought, how perfect? What I appreciate about the sestina form is that there's such discovery.

You have six words that you repeat, and then there's a way of repeating. So you're weaving, weaving the poem, and what I liked about doing this is that I was working to that end word. So you wind up with several stanzas. So I picked the words dreams, jump, holy, back, birth, and bear.

So the poem is built around those words, so it was quite a trick to write a line that would end on dreams. So then, in the next stanza, dreams becomes end line, and the second line, and so on. So this poem is we were there when jazz was invented, and this sestina worked really well for this poem:

"We Were There When Jazz Was Invented. I have lived 19,404 midnights, some of them in the quaver of fish dreams,

and some without any memory at all, just the flash of the jump

from a night rainbow to an island of fire and flowers, such a holy leap between forgetting and jazz.

How long has it been since I called you back

after Albuquerque with my baby in diapers on my hip? It was a difficult birth.

I was just past girlhood, slammed into motherhood. What a bear.

….

What is a Sestina

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sestina

A sestina (also known as sestine, sextine, sextain) is a fixed verse form consisting of six stanzas of six lines each, normally followed by a three-line envoi. The words that end each line of the first stanza are used as line endings in each of the following stanzas, rotated in a set pattern.

Although the sestina has been subject to many revisions throughout its development, there remain several features that define the form. The sestina is composed of six stanzas of six lines (sixains), followed by a stanza of three lines (a tercet).[5][27] There is no rhyme within the stanzas;[28] instead the sestina is structured through a recurrent pattern of the words that end each line,[5] a technique known as "lexical repetition"

The pattern that the line-ending words follow is often explained if the numbers 1 to 6 are allowed to stand for the end-words of the first stanza. Each successive stanza takes its pattern based upon a bottom-up pairing of the lines of the preceding stanza (i.e., last and first, then second-from-last and second, then third-from-last and third).[5] Given that the pattern for the first stanza is 123456, this produces 615243 in the second stanza, numerical series which correspond, as Paolo Canettieri has shown, to the way in which the points on the dice are arranged.[33] This genetic hypothesis is supported by the fact that Arnaut Daniel was a strong dice player and various images related to this game are present in his poetic texts.

Another way of visualising the pattern of line-ending words for each stanza is by the procedure known as retrogradatio cruciata, which may be rendered as "backward crossing".[34] The second stanza can be seen to have been formed from three sets of pairs (6–1, 5–2, 4–3), or two triads (1–2–3, 4–5–6). The 1–2–3 triad appears in its original order, but the 4–5–6 triad is reversed and superimposed upon it.[35]

The pattern of the line-ending words in a sestina is represented both numerically and alphabetically in the following table:

"Sestina"

In fair Provence, the land of lute and rose,

Arnaut, great master of the lore of love,

First wrought sestines to win his lady's heart,

For she was deaf when simpler staves he sang,

And for her sake he broke the bonds of rhyme,

And in this subtler measure hid his woe.

'Harsh be my lines,' cried Arnaut, 'harsh the woe

My lady, that enthorn'd and cruel rose,

Inflicts on him that made her live in rhyme!'

But through the metre spake the voice of Love,

And like a wild-wood nightingale he sang

Who thought in crabbed lays to ease his heart.

First two stanzas of the sestina "Sestina" - Edmund Gosse (1879)

Effect

The structure of the sestina, which demands adherence to a strict and arbitrary order, produces several effects within a poem. Stephanie Burt notes that, "The sestina has served, historically, as a complaint", its harsh demands acting as "signs for deprivation or duress".[17] The structure can enhance the subject matter that it orders

The strength of the sestina, according to Stephen Fry, is the "repetition and recycling of elusive patterns that cannot be quite held in the mind all at once"

LUCY TAPAHONSO on Weaving

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236802011_A_Radiant_Curve_Poems_and_Stories_review

In her sixth collection of poems and stories, 2006 Native Writers Circle Lifetime Achievement Award winner Luci Tapahonso creates a unique compilation filled with intimate family recollections that have given shape to her life and writing. Within A Radiant Curve Tapahonso presents a series of stories and poems that affirm the enduring relevance of Diné oral traditions and the importance of storytelling as integral components to family memory and continuance. Tapahonso begins her stories with a dedication to her youngest grandchildren. She shares with them the origin story of the Diné people: "The first Holy Ones talked and sang as always / . . . They sang us into life" (lines 1, 6). The poet presents her memories—"long time ago stories," as she calls them—as explanations of the Diné way of life to her grandchildren. As a Salt Clan grandmother, part of her duty is sharing the traditions and stories of her people with the young ones, and the poet sets up the proper way to begin to do this in her first poem, "The Warp Is Even: Taut Vertical Loops." Weaving, an integral act in tribal continuance and the preservation of memory, helps Tapahonso to begin the old stories anew. She weaves for her grandchildren, carefully making taut vertical loops as she remembers her own mother, who once wove for her. In recalling these experiences, Tapahonso ensures that both her mother's and the poet's own memories are solidified in the creative process. Of equal significance, Tapahonso's weaving echoes the relationship between her people and the earth, setting their stories down with the new story of those for whom she weaves.

The warp is even: taut vertical loops

- by Lucy Tapahonso

Source: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/208/monograph/chapter/3086515/pdf

The warp is even: taut vertical loops between our father and the earth.

Today I began anew: in the gray pre-dawn the air is moist.

As I walk, my footsteps echo in the still morning; damp, fragrant circles appeared overnight on the cold driveway. Soon they will vanish with the sun’s first rays, but now I breathe the sweet dampness.

Suddenly I miss my father so. How he savored such mornings.

He would have spoken to the solitary dove that sits on the edge of the red tile roof.

Its long, delicate coos are the rhythmic pauses of desert mornings.

Today I began anew. This afternoon, after phone calls and class preparations,

I sit in the bright sunlight and twist, then loop the dark edging cords along the top and bottom of the loom.

My fingers move easily between the turns of yarn: such needed slants of rain. “It hasn’t rained here for months,” I tell the loom.

On a clear, quiet afternoon last spring, my mother said, “It’s hard to see now; my eyes are getting weak.” It seemed that she had been thinking of this for some time.

Today, the tightly spun dark red yarn falls into place evenly.

I began anew for my mother, and some things she remembers as she looks at rugs:

The long afternoons decades ago when the children slept, the soft tamping of her batten comb echoed in the small house.

The intricate double-sided rugs her mother-in-law wove. Even now, 70 years later, she marvels at the saddle rug Nihinálí ’Ásdzą́ą́n made for her husband, my father. I began anew for my mother’s memories.

Today, I began anew. On the mantel is the small basketball my grandson left when he last visited.

I look down the bright hallway and recall his bubbling baby laughter. His dark, shiny eyes glitter with delight.

I easily recall the warm tautness of his little body in my arms. His black, thick hair against the bend of my elbow.

He lets me carry him as if he were an infant. I sing old songs, and he watches me. He watches the huge blue sky overhead.

I sing songs created for him, “Whose little boy are you? Said I am grandma’s boy. Grandma’s little baby boy.”

As he listens intently to the songs and watches the skies of his homeland, I memorize everything. I wish for such moments every day.

I weave the first four rows of black yarn for my little grandson, who inherited my father’s name: Hastiin Tsétah Naaki Bísóí.

The warp is even: taut vertical loops between our father and the earth.

The Sestina Project

Source: https://www.public.asu.edu/~aarios/formsofverse/anecdotes/page9.html

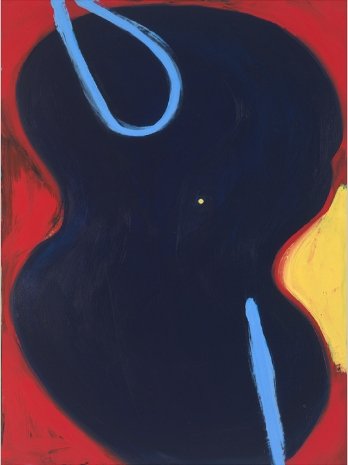

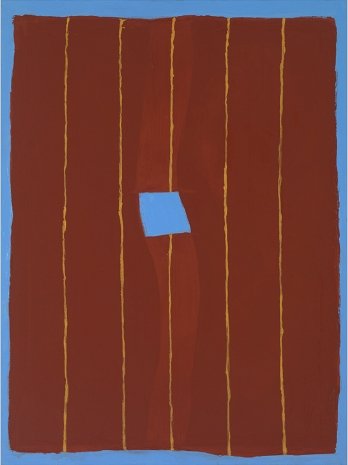

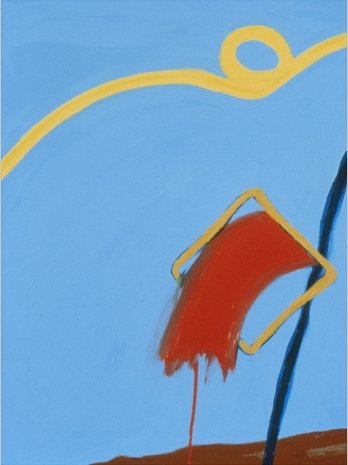

The Sestina Project is a visual equivalent of various sestinas by poets including John Ashbery, Honor Moore, Judith Kroll and her partner in the Sestina Project, Mary Pinard. It was exhibited in Boston at the Trustman Art Gallery at Simmons College from March 16 until April 30, 1999.

The effect of the sestina is meditative and kaleidoscopic. In her various size wall pieces, artist Jane Kamine visualizes the poetic form of sestina poetry in both figurative and abstract images expressive of the poem itself. In response to the poetry's evocation of rhythm and cadence, Kamine substitutes colors, patterns, and pictographs for the end words in sestinas.

Strangely enough, The Sestina Project is not the only effort to consider this form in relation to the visual arts. In a terribly dry article, Robert Druce compares his process of writing a sestina to the weaving of a particular ancient tapestry.

Source: http://janekamine.com/p_sestina_g.html

Artist Jane Kamine / Paintings / Sestina series